Published : 2025-11-13

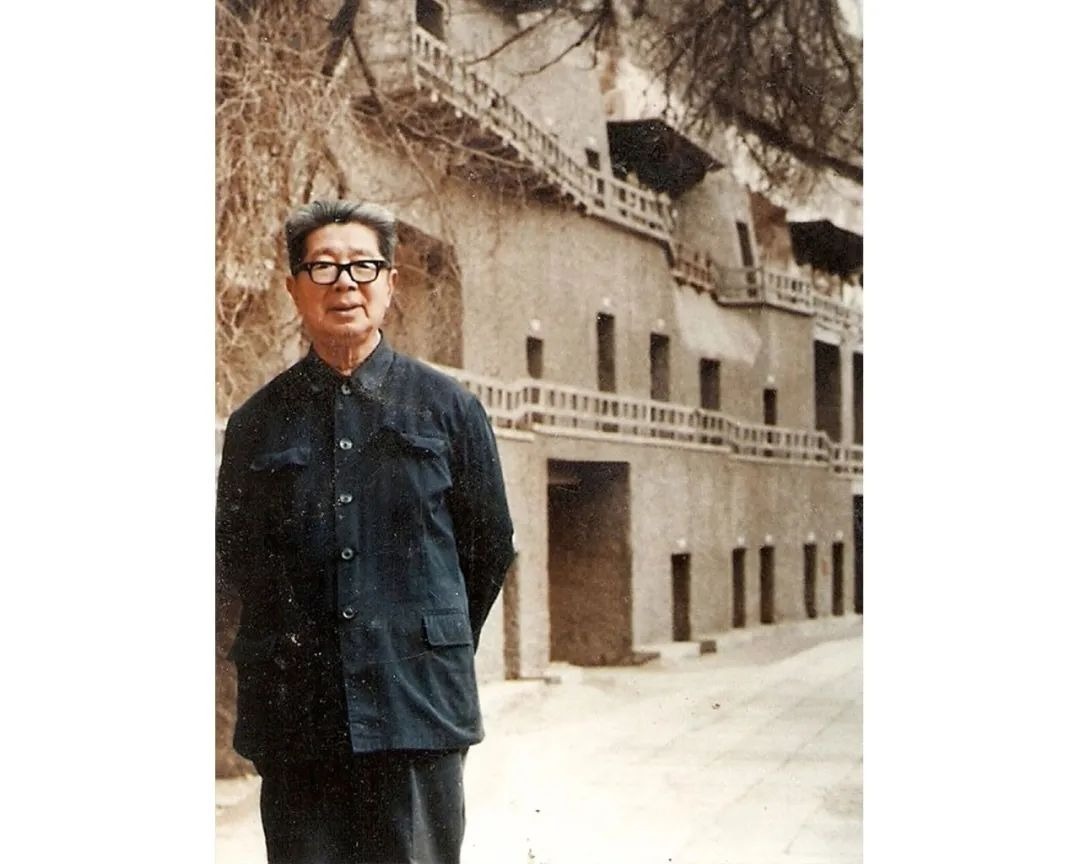

The Dunhuang Academy has been established for over 80 years. Looking back on these 80 years, its first director, Chang Shuhong, is a pivotal core figure.

Even today, people often exclaim: it is unimaginable whether Dunhuang would still have such splendour today without Chang Shuhong, without his perseverance and dedication.

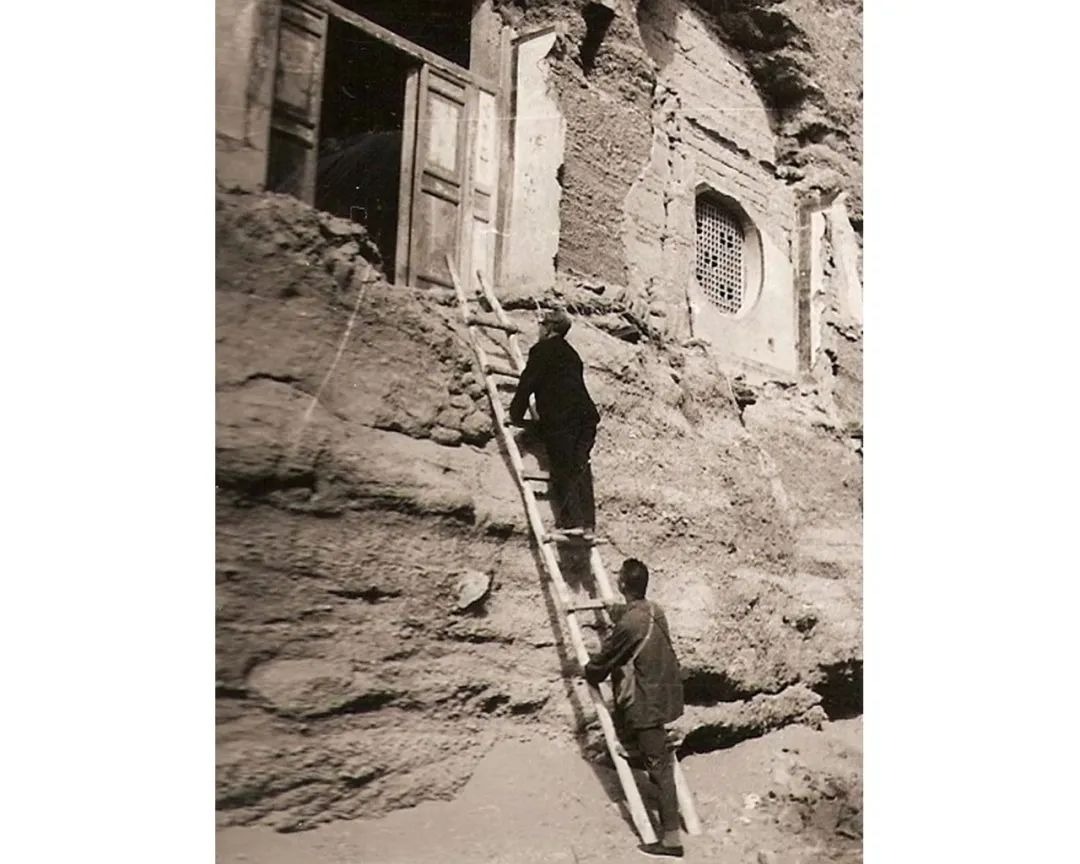

Arriving in Dunhuang to clear accumulated sand for the Mogao Caves

In March 1943, when China was facing both internal and external troubles, Chang Shuhong and his party resolutely came to Dunhuang to protect the cultural heritage.

However, the first task that greeted these artists upon their arrival was manual labour: clearing away drifting and accumulated sand.

The Mogao Caves are located in the Gobi Desert. Whenever the wind blew, sand would be swept in; coupled with years of accumulated sand, the environment was truly harsh. The hired local labourers found it too arduous and left one after another.

Chang Shuhong had repeatedly reported to the Nationalist government, hoping the county government would take action to control the drifting sand, but after perfunctorily dealing with it with a few silver dollars, the county government made no further response.

So Chang got his hands dirty, making a tool called a "sand-pulling rake" to push the accumulated sand row by row to the edge of the water channels, and then released water to wash the sand away.

He also led everyone in building a 2-metre-high, 2,000-metre-long sand wall in 50 days, which firmly protected the caves, isolating them from drifting sand and livestock.

Read more: "The Dunhuang Devotee" Chang Shuhong, who left France for the desert

Read more: "Daughter of Dunhuang" Fan Jinshi, the guardian of Chinese culture

Chang Shuhong raced against time to conserve the caves

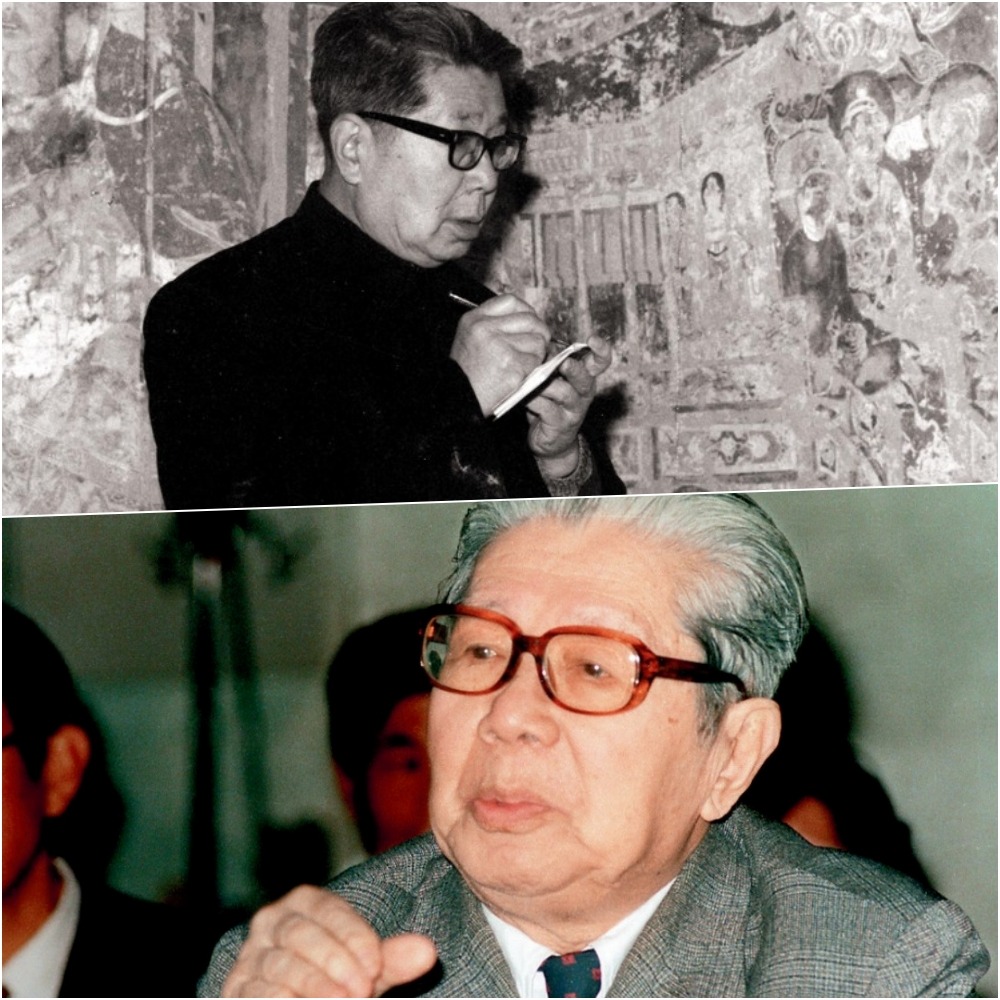

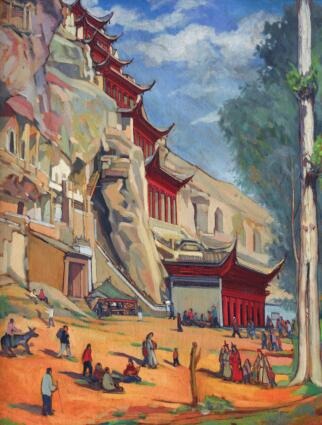

The Mogao Caves have suffered from erosion by wind, sand, and the environment, continuously deteriorating and vanishing. Besides maintaining the surrounding environment, the most urgent task was to copy the murals.

At that time, there was no photography or digital technology, so it was all up to the painters to "copy" the murals stroke by stroke.

Some people suggested that making rubbings directly on the walls would save a lot of effort, but rubbing requires nailing the paper to the wall and outlining with a pencil, which would damage the fragile walls, so Chang Shuhong stipulated that they could only copy by sight.

There was no lighting in the caves, and it was very dim. The painters worked on small stools, holding an oil lamp in one hand and a brush in the other, illuminating, looking, and then painting one stroke at a time.

When copying the murals on the cave ceilings, their heads and bodies were at an almost 90-degree angle, and over time, they would inevitably feel dizzy and muddle-headed.

When the pigments ran out, they used ancient methods to source materials locally, adding binders to soils of different colours to create various pigments...

In this arduous environment, they copied a large number of mural works, which became important materials for the conservation of Dunhuang.

The sense of loneliness was the hardest to endure

However, the pervasive sandstorms and arduous environment could be overcome, but the loneliness and isolation from society were more fatal.

The painter Chang Dai-chien (張大千), who once copied murals here, described the conservation work as a "life sentence".

One summer, a colleague in the work team developed a high fever and needed to go to a hospital in a nearby town. Before being put on an ox-cart, he tearfully said to Chang Shuhong, "After I die, don't throw me into a sand pile..." The young man later recovered from his illness and left the Mogao Caves.

Chang Shuhong's wife, Chen Zhixiu (陳芝秀), also found it difficult to endure her husband's busy schedule and the harsh environment. A few years later, she chose to abandon him and their two children, leaving the great desert alone. Chang Shuhong was devastated, but he resolutely stayed behind.

Later, he married his assistant, Li Chengxian (李承仙), and they supported each other through hardship in the days that followed.

Rescue work fully launched after the founding of New China

After the founding of the People's Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, Chang raised a red flag in front of the ancient Thousand Buddha Grottoes (千佛洞), and the rescue and restoration work at the Mogao Caves was fully launched.

In April 1951, Chang Shuhong brought all the copied murals and important cultural relics to Beijing and held a grand exhibition of Dunhuang's cultural relics at the Meridian Gate of the Forbidden City.

Premier Zhou Enlai personally visited the exhibition and, upon learning of the arduous working conditions at the Mogao Caves, despite the extreme financial difficulties, he allocated funding of 200 million yuan (old currency, equivalent to about 20,000 RMB today) to equip the site with a generator and a jeep, bringing electric lighting to the Mogao Caves for the first time.

In the same year, the Dunhuang Art Research Institute (敦煌藝術研究所) was renamed the Dunhuang Cultural Relics Research Institute (敦煌文物研究所), with Chang Shuhong as its director.

Afterwards, he successively held exhibitions in countries such as India, Burma and Japan, showcasing the beauty of Dunhuang art to the entire world.

Read more: How many types of grottoes are there in the Mogao Caves?

Devotion without regret: To be Chang Shuhong again in the next Life

During the subsequent Cultural Revolution, Chang Shuhong suffered much injustice and cruel treatment, but that experience is not recorded in detail in his memoirs.

Over the years, he persisted with the conservation work at Dunhuang. With his colleagues, he searched for artefacts, copied murals, numbered the grottoes... He also conducted systematic and detailed research and preservation of Dunhuang art.

In addition, he also wrote a number of papers of high academic value, organised large-scale exhibitions, published art catalogues, and strived to introduce Dunhuang art to the whole world.

On 23 June 1994, "The Guardian of Dunhuang", Chang Shuhong, passed away, and his tombstone was erected on a sandy plot in front of the Mogao Caves.

Japanese author Ikeda Daisaku (池田大作) once asked Chang what profession he would choose if he were to return to the world in his next life.

Chang Shuhong replied, "I am not a Buddhist and I do not believe in reincarnation. But if there really is a next life, I shall still be Chang Shuhong, and I will complete the work I wanted to do for Dunhuang but have not yet finished."