Published : 2025-10-21

Chinese clothing culture has a long history, and Hong Kong's "Traditional Craft of Making Chinese-style Clothing" is recognised as a national Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH).

Here, "Chinese-style clothing" refers to the Chinese cheongsam (長衫, meaning "long gowns") for both men and women, with the women's cheongsam specifically known as the "qipao" (旗袍).

In Hong Kong's intangible cultural heritage list, the craftsmanship of making Chinese cheongsam and wedding attire, such as Kwan Kwa (裙褂), is equally highlighted.

Below, we will introduce the characteristics of this traditional handicraft through 10 key facts.

1 type of formal attire

According to Hong Kong's Intangible Cultural Heritage database, the Chinese cheongsam began to gain popularity in the early Republican period.

After the Xinhai Revolution (辛亥革命) in 1911, the Republican government promulgated the "Dress Code" decree in 1912, listing the cheongsam as one of the formal attires for men.

It essentially defined the form of the men's cheongsam, which includes: a straight collar, narrow sleeves, a right-over-left front placket, an ankle-length hem, and a slit on each side at the bottom.

Cheongsam holds significant social meaning in the traditional clan societies of the New Territories in Hong Kong, serving as a status symbol for the elders.

2 types of business models

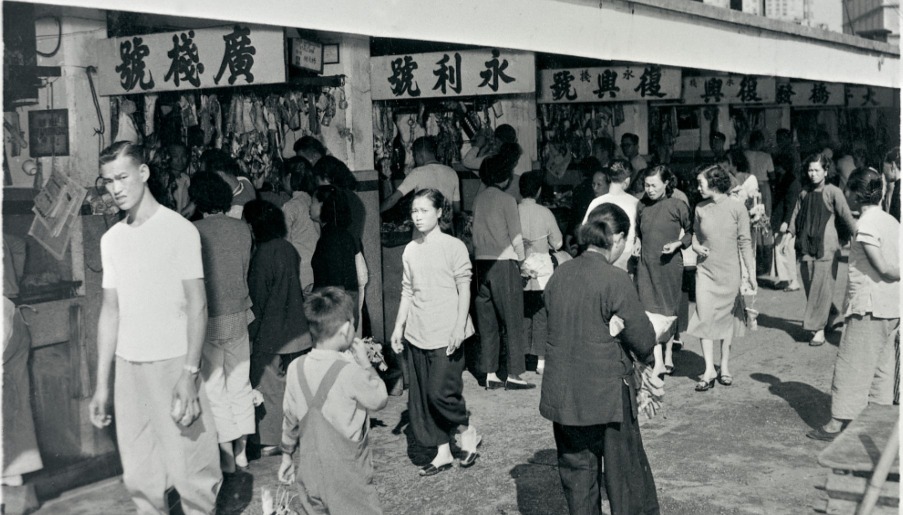

In the mid-1950s, cheongsam tailors mainly operated in two ways. The first was the "carryall tailor" who went door-to-door for business, handling everything from soliciting customers to making the garments.

The other was tailors employed by workshops, often affiliated with silk or department stores. Customers would go to the silk and satin companies to buy fabric, and the company would outsource the tailoring orders to workshops. However, some companies employed their own in-house tailors.

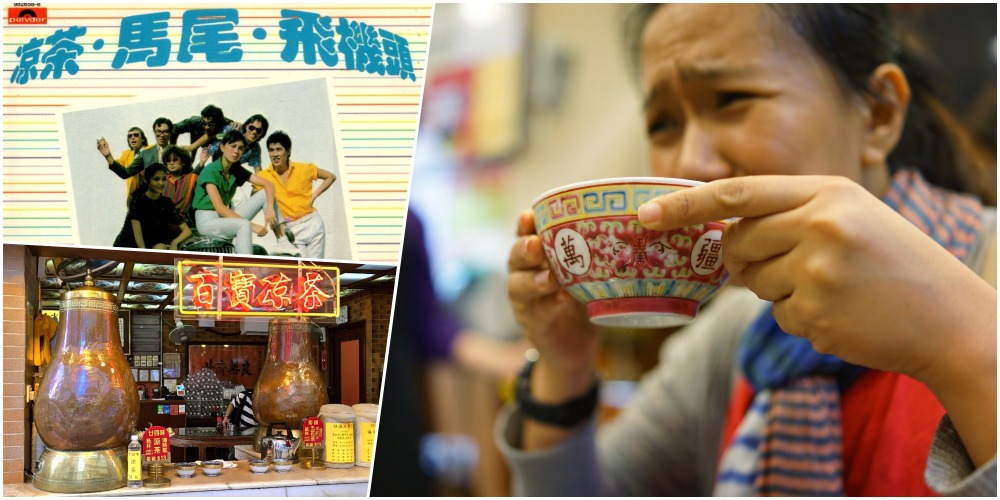

3 major reasons for the decline

The decline of cheongsam can mainly be attributed to three major reasons:

Firstly, trends changed. In the 1960s and 70s, influenced by Western popular culture, young people began to favour fashionable attire such as jeans and Western-style dresses and skirts, and the number of people wearing cheongsams gradually decreased.

Secondly, competition from ready-to-wear clothing. Traditional cheongsams were custom-made by hand, making their costs incomparable to mass-produced, inexpensive ready-to-wear garments. Furthermore, as the labour fees of cheongsam tailors became increasingly expensive, the price of cheongsams soared.

According to industry insiders, in the early 1980s, a custom-made sleeveless cheongsam cost between 1,200 HKD and 2,200 HKD, becoming a luxury item that was unaffordable for ordinary people.

Thirdly, the loss of skilled professionals. Changing in fashion trends and rising costs led to a sharp decline in the cheongsam business, with many tailors facing unemployment or career changes.

By the 1980s, the number of cheongsam practitioners in Hong Kong plummeted from a peak of over 1,000 to just over 400. Cheongsam shops began to disappear from the city, with their numbers falling by 80% from over 200 to just a few dozen.

4 types of women who wore cheongsam

Women's cheongsam, also known as "qipao" (旗袍), is generally believed to have evolved from Qing Dynasty (1644-1911 AD) clothing.

The popularity of qipao in the 1920s was actually related to a women's awakening movement.

At that time, China was influenced by Western thought and the New Culture Movement. The traditional concept of male superiority was gradually dismantled, and women of the Republican period began to imitate men by wearing the cheongsam, symbolising their pursuit of freedom and equality.

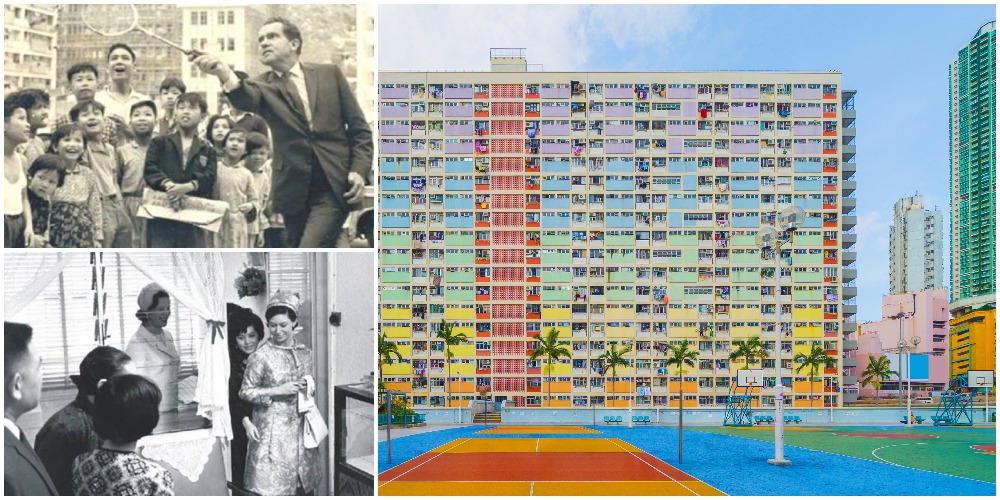

There were mainly four types of women who wore the qipao at the time. The first type was female intellectuals, such as teachers and students, whose cheongsams were typically simple and modest.

The second type was well-bred ladies and the wives of socialites, whose cheongsams were made of high-quality materials and had a more conservative, loose-fitting design.

The third type was singers, actresses, and celebrities, whose cheongsams were not only made from luxurious materials but were also fashionable, with a form-fitting designs that accentuated the female figure.

The last type was courtesans in brothels, whose cheongsams were mostly exquisite and glamorous, designed to please their clients.

The heyday of qipao in 1950s

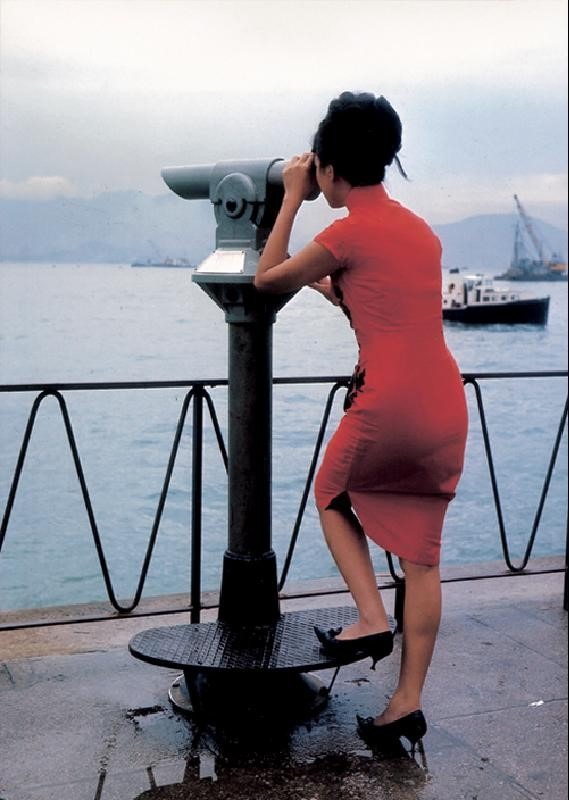

The 1950s can be described as the heyday of the cheongsam. With the improvement of women's status and educational level, more and more women entered the workforce.

Before the mass production of Western ready-to-wear, cheongsam was their daily attire, which made cheongsam more common and popular, and the styles also became increasingly sophisticated.

In the 1950s, cheongsam began to adopt Western three-dimensional tailoring methods, incorporating the concept of the three measurements, making them more form-fitting.

Entering the 1960s, cheongsam styles became even more close-fitting and shorter, further accentuating the graceful beauty of the female form.

However, the male cheongsam gradually declined in popularity in the 1950s, replaced by Western-style suits.

The golden era of kwan kwa in the 1960s

Hong Kong's Representative Intangible Cultural Heritage list places the craftsmanship of making kwan kwa (裙褂, traditional Chinese wedding attire) alongside that of Chinese cheongsam.

The golden age of the kwan kwa was from the 1960s to the 1980s, when the baby boom began to reach marriageable age. As wearing Western-style wedding dresses was not yet popular in Hong Kong at the time, most brides chose to wear kwan kwa for their weddings.

According to old newspapers, kwan kwa was in such high demand that it often went out of stock.

The decline of cheongsam in the late 1970s

After the World War II, Hong Kong's industry took off, and the garment manufacturing industry in particular boomed, impacting the traditional tailoring trade.

Young people, eager to follow the trend, switched to wearing Western-style dresses, skirts, and jeans, leading to the decline of the cheongsam in the 1970s. Few people would still spend time selecting fabric and find a tailor to have a cheongsam custom-made.

8 types of tailoring tools

As a national Intangible Cultural Heritage, the technique of making Chinese cheongsam requires specific tools, which can be summarised into eight main types.

First are the measuring tools, including a soft tape measure for body measurements and a tailor's ruler for measuring cloth. The measuring tool used by tailors is the Guangdong tailor's ruler, also known as "Tong-chek" (唐尺), with 1 Tong-chek being equal to 37.25 cm.

Second are the marking tools, which include triangular chalk blocks and a "chalk bag" containing crushed chalk powder.

Third are the cutting tools, such as scissors and a cutting table. Fourth are the ironing tools, including an iron, an ironing stand, a water spray bottle, and wax blocks. Wax is applied to sewing threads before ironing to make them smoother and less prone to tangling.

Fifth are the adhesion tools, such as glue and scrapers. Sixth are the sewing tools, which include a sewing machine, sewing needles, and a "thimble" to prevent being pricked by the needle.

Seventh are the fastening tools, and the eighth type includes miscellaneous tools, such as paper sheets that some tailors place between fabric layers to avoid piercing the lower layer while sewing.

9 pieces of fabric to make a kwan kwa

Kwan kwa is divided into an upper jacket (褂, kwa) and a lower skirt (裙, kwan). Nowadays, very few people have them custom-made; they are mostly rented, so they do not need to be form-fitting, making their cutting and sewing completely different from that of a cheongsam.

A set of kwan kwa consists of a total of 9 pieces of fabric: 2 for the front lapels, 1 for the back, 1 for each of the 2 sleeves, and a total of 4 pieces for the front, back, left, and right of the skirt.

It takes at least two to three months to make a set of kwan kwa, depending on the amount of embroidery. The embroidery reflects the value of the kwan kwa, and therefore requires the most meticulous attention.

10 steps to make cheongsam

According to the ''Hong Kong Intangible Cultural Heritage Series: The Craftsmanship of Making Hong Kong-style Cheongsam and Kwan Kwa", the process of making a men's cheongsam can be broadly divided into 10 steps:

First, measurements are taken, including neck circumference, shoulder width, bust, waist, hips, and body length. The second step is to prepare the fabric. Thirdly, tailors use chalk lines to draft patterns onto the fabric.

The fourth step is "pattern alignment", where patterned fabrics are checked to ensure the patterns align seamlessly at the seams. Fifth, the fabric is cut along the drafted lines. In the sixth step, fabric is ironed flat, and starch paste is applied to specific areas to aid shaping, positioning, and sewing.

The seventh step is to attach reinforcing and supporting strips along the edges of the garment, the lapels, and the two sides under the arms. The eighth step is to sew the fabric and the lining together. In the ninth step, the collar is crafted for the cheongsam.

As for the final step, buttons are attached to the cheongsam.

For women's kwan kwa, the process involves up to 14 steps, including "pleating" to enhance the curved, three-dimensional silhouette, adding interfacing to the collar and cuffs, attaching the lining, shaping the collar, binding edges, sewing, and finally attaching zippers and buttons to complete the work.

Read more: 8 numbers that unveil HK's Tai Hang Fire Dragon Dance